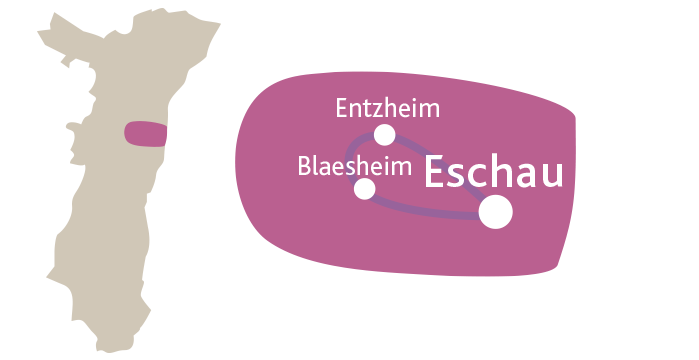

Eschau

Église Saint-Trophime

Présentation

En 929, les Hongrois détruisirent l’abbaye que Rémi, évêque de Strasbourg, avait fondée en 770 pour y déposer les reliques de saint Trophime et sainte Sophie. Le monastère a été rétabli dès 996, mais la sobre église actuelle date essentiellement de la 1ère moitié du 11e siècle. À l’extérieur, seule l’abside est décorée de fines arcatures. L’intérieur est caractéristique du premier art roman Alsacien, tributaire de l’architecture ottonienne : plan basilical, nef plafonnée reposant sur des piliers carrés, transept à croisillons bas. Du cloître du 12e siècle, il reste de très belles parties au musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame à Strasbourg. A découvrir : le jardin monastique, face à l’église.

Galerie photos

En savoir plus

Eschau est située sur l’ancienne voie romaine reliant Bâle-Augst à Strasbourg. L’abbaye Sainte-Sophie fut fondée vers 770 par trois membres de la famille ducale d’Alsace : Rémy, évêque de Strasbourg, Adala, première abbesse d’Eschau, et Roduna, moniale. Le monastère, détruit par les Hongrois en 926, est reconstruit par l’évêque Widerold autour de 996. Un cloître remarquable est érigé vers 1130 au nord de l’abbatiale. Avec des fragments retrouvés lors de fouilles archéologiques, le musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame en présente à Strasbourg une reconstitution partielle. En 1143 l’abbaye fonda sur la « route romaine » passant à Eschau « un hôpital pour pèlerins de toutes parts venant ». Depuis 1989, un jardin monastique de plantes médicinales fait revivre cette activité caritative et médicinale des moniales.

Cette construction représentative de l’architecture ottonienne trouve ses racines dans l’art impérial de Charlemagne. Saint-Trophime diffère des autres édifices à piliers et plafonds charpentés, comme ceux d’Avolsheim ou d’Altenstadt. Elle rappelle d’autres basiliques ottoniennes comme celle de Reichenau ou d’Hildesheim.

Saint-Trophime est considérée, à cause de ses volumes et de ses proportions, comme un édifice représentatif du premier art roman alsacien, se rattachant à l’architecture carolingienne-ottonienne. Plusieurs particularités la distinguent des églises romanes ultérieures. La nef centrale est deux fois plus large que les bas-côtés. La croisée rectangulaire est délimitée par deux arcs diaphragmes hauts et deux arcs plus bas ; le transept, plus bas que la nef, est un trait de l’architecture carolingienne. L’abside, directement soudée à la croisée, est d’une dimension monumentale. Ce jeu de formes et de dimensions s’avère caractéristique de l’architecture ottonienne.

Elévation : Six arcades sur piliers carrés séparent la nef centrale des bas-côtés. Les six fenêtres percées à l’origine dans les murs gouttereaux de la haute nef ont disparu, remplacées par des ouvertures pratiquées au 18e siècle. Seuls les piliers et les arcs de la croisée sont en pierre de taille, tout le reste de l’édifice est composé de maçonneries en petit appareil.

Volumes et proportions : En dehors de la seule abside voûtée en cul-de-four, tout l’édifice présente des plafonds charpentés. La largeur des bas-côtés correspond exactement à la moitié de celle de la nef centrale. La croisée est de plan rectangulaire. On trouve à l’extrémité ouest des bas-côtés des traces de compartiments carrés. Les proportions d’origine de l’édifice ont été légèrement altérées. Par rapport aux volumes primitifs, le niveau actuel du sol est supérieur de plus d’un mètre.